During our lives we go through many different learning experiences. We learn at many different moments and in many different ways. And what people learn and who teaches it varies greatly from culture to culture. Indigenous children, for example, learn a great deal from their parents and close relatives such as brothers, sisters and grandparents. Knowledge about how to do things may be passed on during day-to-day activities or on special occasions such as rituals and festivals.

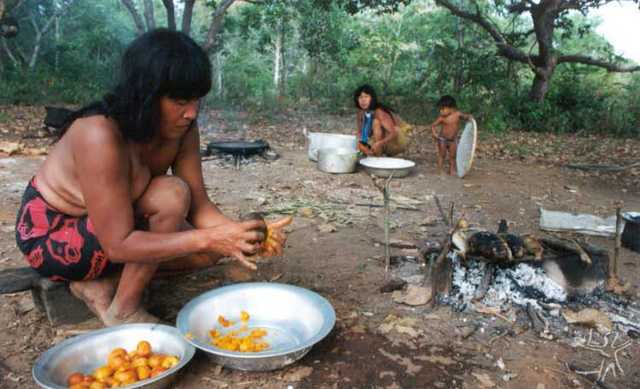

Children learn most, however, from their immediate family. When their relatives do things they join in with them. They pay careful attention to what the older people do and say. They go with their parents to the village gardens where crops are grown. They go fishing with adults and have fun playing! Each game is a way of learning a skill that will be useful to them in the future, such as how to hunt, fish, do body painting, or how to make bows and arrows, pots and baskets... It is through this learning process that children develop the skills they will need to carry out the activities for real in the future.

Children learn how to behave and relate to others in their family and community by living side-by-side with older people. They learn, for example, who should be treated like brothers and sisters or aunts and uncles, and who they could get married to later in life. They find out what their own importance is within the community. Little by little, children learn ways of behaving, principles and all the things that are important for making them active, participative members of a community. This is why it is very important that they pay close attention to everyday life around them, to what they are taught and the knowledge passed onto them.

Do indigenous villages have schools?

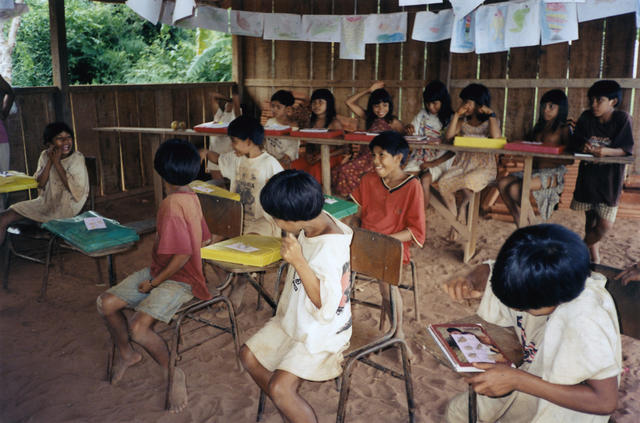

- Yes, many villages have schools! As is explained elsewhere on this site, most indigenous villages are located on areas of indigenous land. And each area of indigenous land may have one or more school. It depends how big it is, and what each community is like.

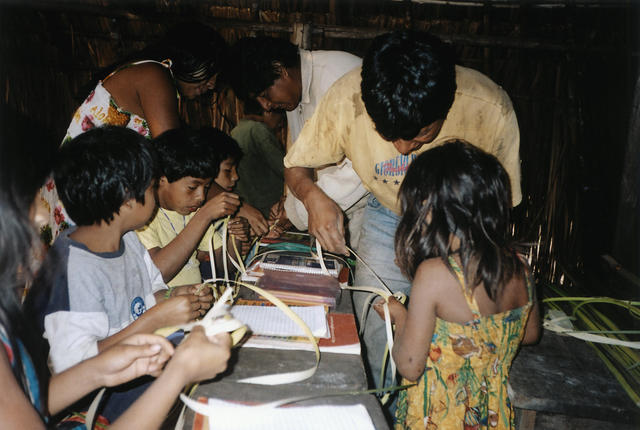

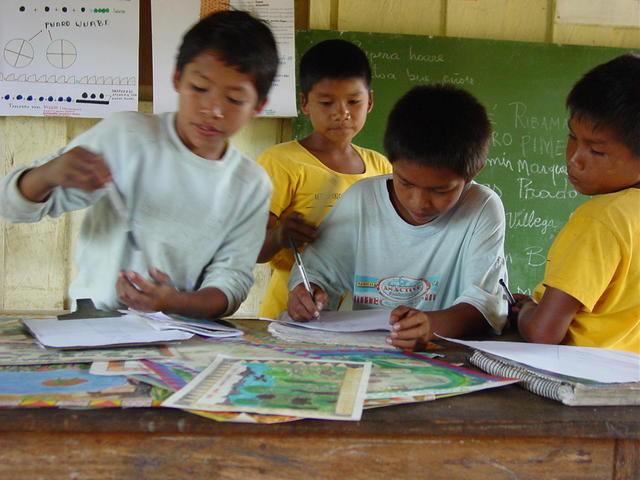

Ana Cecilia Venci Bueno. Just like non-Indian schools, indigenous school are spaces where children go to learn. And very often, what is taught in indigenous schools is very different to what is passed on by relatives in the village. Of course, the two types of learning have things in common. But basically teaching in schools focuses on reading, writing, numeracy and other forms of learning that will be important when children have contact with the non-Indian world. Meanwhile relatives pass on knowledge about how the community is organized, how artefacts are produced, and how to live well in the environment around them.

Aloisio Cabalzar. The subjects that indigenous children learn at school are usually somewhat different from the subjects learnt by non-Indian children. Indigenous peoples have the right to make their schools different to other schools. Their teachers can teach subjects which pass on information about the children’s own culture and language. But this right is not always put into practice. Often the teachers and the books used in indigenous schools cover things that do not have anything to do with the actual daily life of the indigenous community around them. In fact, they may give the impression that the only correct view of the world is a non-Indian one.A look at the history of education in Brazil’s indigenous schools shows that they have, on the whole, tried to integrate indigenous populations into the society around them. In other words, they have put pressures on indigenous children to become part of the wider culture of the country. And this integration has, in fact, often been a way to force Indians to live like non-Indians. So they would, for example, be taught to read and write just in Portuguese, the official language of Brazil. It is only recently that indigenous languages began to be used in schools.

Can schools help strengthen the use of indigenous languages?

New kinds of indigenous schools started to develop in the 1990’s. They started to attach importance to cultural differences and to indigenous languages. Because of this, they became places where the use of indigenous languages was stimulated and encouraged.

Rosana Gasparini. From this moment on, indigenous peoples themselves could become teachers in village schools. Indigenous languages began to be used in the classroom. And the subjects taught began to change. They became more relevant to the reality of life of the community around the school.

Acervo ISA As well as concentrating on reading, writing, numeracy and other basic skills that non-Indians learn, indigenous schools started to teach other more local forms of knowledge. Pupils might learn, for example, how to use natural resources and look after the environment around them. They might study the history of their ancestors. They might hear their own people’s myths etc. As well as this, the calendar of the school year was adapted to fit in with local festivals and rituals. This new model of education helps give importance to local languages and also to the children’s sense of belonging to an indigenous group with a particular way of life. This is because they learn things that refer to their lives and to the life of their own community.

Why is it important for indigenous people to learn Portuguese?

Even if lessons at school are in an indigenous language, it is very important that children also learn Portuguese. Being comfortable with Portuguese gives indigenous people a way to communicate with others and to translate and understand the laws that govern life in Brazil (in particular, those laws which set out rights for indigenous peoples). The fact is that all the documents you need to live as a Brazilian citizen are written in Portuguese. Being able to write in Portuguese is helpful to indigenous people in various ways. It means they can defend their rights. And it gives them access to the knowledge of other societies.

How the Xavante learn?

Camila Gauditano The Xavante, who live in the cerrado environment of the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso, call themselves A’uwé. In the Akwén language this means "people". For the Xavante, learning is a process which goes on throughout their lives, from childhood through to old age. At each stage of this long journey, new things are learnt. And the learning happens in many different situations. Some happens during moments specifically meant for learning, such as rituals. Other things are passed on through the activities of day-to-day life.

Camila Gauditano The most ordinary things in everyday life are considered to be important chances to learn by the A’uwé. Children usually wander freely around their village in the company of other children, or elders, or adults. As such, they become part of a whole range of activities. And this is how they notice, and learn, the rules which shape their community.

Camila Gauditano Domestic chores are learnt on a day-to-day basis. When children help their relatives by looking after a younger brother or sister, or washing clothes, or taking messages, or preparing food, they are playing and having fun. But little-by-little they are also learning.Play is a way of learning. For example, boys learn to make bows and arrows when they are still very young. And they play at being hunters and animals around the houses where they live. This way they gradually get better at making bows and arrows so that by the time they are older, they can make beautiful bows and arrows for hunting. Through their games they also develop the physical qualities you need to be good hunters.

Camila Gauditano. Xavante children generally play the same game over and over again. Each time they play it, they discover new abilities and new challenges. This way they develop their skills. And they learn about possibilities inside them and around them in the wider world. Making a pretend house would be a good example of this. Sometimes Xavante children like to make a little make-believe house out of mud. When they do, they divide it up in the same way as a real house. This way, they think about how domestic life is organized in their village. And they deepen their knowledge of their community.

Rituals are other important moments for learning. During rituals everyone learns. Young people learn about the principles, values, of their community and how to live within it. And adults learn details about how to carry out the ritual from the elders.Ritual occasions set out to make clear the social divisions and rules of Xavante society and to strengthen people’s knowledge of them. They are also ways of drawing attention to changes in people’s lives. They mark journeys from one sort of life to another. This might be the change, for example, from being a child to being an adult. The people who take part in these ritual journeys (or “rites of passage”, as they are often called) learn how to act within their society. They learn what the community expects of them and how to behave from then on. These rituals have concrete objectives such as demonstrating that boys can deal with physical challenges, that they know important songs, that they are a part of the A’uwé system of exchange etc.As well as these ways of learning, the Xavante attach importance to studying at school. They know that this is an important way of developing an understanding of the world outside of the village. They see it as a way to gain other kinds of knowledge and to become skilled at using technologies used by non-Indians.

How the Yudjá people teach

Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2006. The Yudjá, who are also known as the Juruna, live in the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso and Pará, near to the River Xingu. The text below was put together in 2008 by Yudjá people from the village of Tuba Tuba, which is in the Xingu Indigenous Park.

Our way of teaching

Katia Ono/ISA, 2006. The Yudjá people use education to teach young people how to work and behave well. Young people learn from practical experience. They observe how something is done. They look and listen attentively. Then they may imitate what they have seen, or play at doing something like an adult. It is important for them to show curiosity and ask questions with a desire to learn. Parents give advice to their children at night time. They talk to them before they go to sleep and they tell old stories which pass on knowledge.

It is also the time when young people learn from their family by watching relatives at work. They imitate them and try out things for themselves. A child of 5 to 8 years old can begin to help with work in a number of ways. This might mean spinning cotton, weaving, making small bows and arrows and going with their parents to fish and to parties.

Paula Mendonça/ISA, 2005. But some types of work are not allowed until you are about 10 years old. When a girl turns into an iparaha (an adolescent), she goes through a period of preparation called reclusion. During this time, she will broaden and strengthen her knowledge of traditional stories, of how to behave, and of special medicines which she needs to grow up healthily. She will also learn work skills such as pot-making, weaving, painting, traditional recipes, how to plant crops, work on a garden, keep a house, hunt, fish and other things. This is how she gets ready for the day she will marry and pass on her knowledge to her own children.

Katia Ono/ISA, 2006. School education needs to happen alongside the traditional education of the Yudjá people. Schools should teach writing and the way that non-Indians speak, so that a person will be able to communicate with speakers of other languages. It should also teach how to write our language and strengthen our culture. Everyone should take part in school life: the school-children, the parents of the school-children, the teachers, older people, younger children, adults, teenagers, all the community.

What do the Kisêdjê learn from the elders of their community?

The Kisêdjê, who are also known as the Suyá, live in the Xingu Indigenous Park. The word Kisêdjê means listen, understand and know. They attach great importance to being able to do these things. In the text below, taken from the book Ecologia, Economia e Cultura (2005), they describe what is learnt from the elders in their community.

Values in Kisêdjê society

Values are taught to us from childhood. They are passed on by elders, grandparents and parents. We are taught to respect people, behave well, hunt, fish, and value the natural world and human life. We learn how to treat guests, close families and more distant families. We discover how to make handcrafts, to respect animals and the other beings that exist in nature. We learn to be generous and honest human beings. We learn to follow the rules that the elders pass on when they teach us. We are taught to respect the places and objects which appear in the stories told to us by the elders. There are sacred places and objects. The most sacred place and objects are those used for the shaman’s prayers. He has a whistle made from the bone of a bird. He has a special cigarette. He has herbs. Many people respect shamans and regard them as sacred people. The mountains and lakes are also sacred. They have their stories told by the elders.

Sources of information

- Associação Terra Indígena do Xingu (ATIX) e Instituto Socioambiental (ISA)

Ecologia, Economia e Cultura - livro 1 (2005).

- Programa Xingu - Instituto Socioambiental

Projeto Político Pedagógico Povo Yudjá, aldeia Tuba Tuba (2008).

Portugues

Portugues

German

German

Spanish

Spanish

Norwegian Bokmål

Norwegian Bokmål

Games

Games Myths

Myths Food

Food How they live

How they live Ilya e o fogo

Ilya e o fogo String figures: Ketinho Mitselü

String figures: Ketinho Mitselü Toys and games of the Kalapalo: Ikidene

Toys and games of the Kalapalo: Ikidene